Disclaimer: The characters in this story are triathletes. Any relation to persons either alive or dead, or half-dead, is purely coincidental. Names may have been changed to protect identities. Or not.

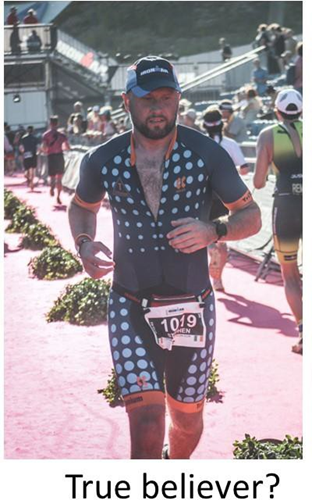

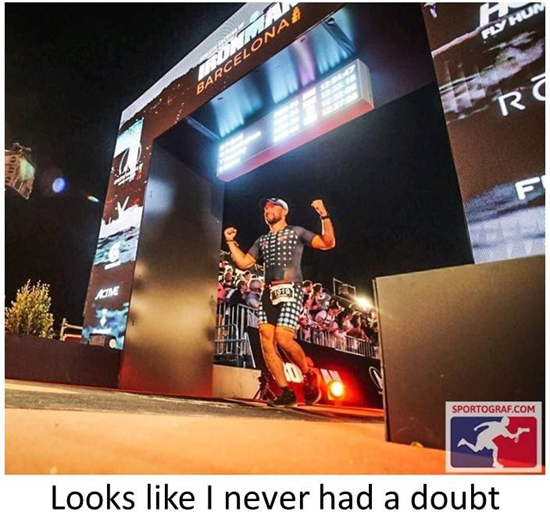

The photos I’ve included here aren’t the ‘effortless’ ones I uploaded to Strava. What you’ll see is the true face of Ironman.

I can’t really remember why I signed up to do an Ironman. Perhaps it’s because I’m 43 and while I’m happy with everything I’ve accomplished in life, there are many things on my bucket list I haven’t managed to do. Enough of them to fill an Ikea warehouse. I still haven’t legally driven a JCB, nor have I done a sky-dive. I haven’t been on a motorbike, because my mother warned me they were death traps. And I haven’t taken a year out to go traveling. Ironman was never on my list. Only achievable things went on the list. Ironman seemed like the sort of thing that was done by people who hated themselves*. Perhaps I signed up for it because in 2020 I somehow wandered into the club looking for a new challenge. Through the club, I managed to do a sprint triathlon, which is why I signed up for an Olympic distance, and when I was done with that I completed a half Ironman, and then another. Perhaps it’s because I wanted to see how far I could push the boundaries of my physical endurance. Could I find my limit? How far could I push myself before I broke*.

*Yes. The irony.

I arrived into Barcelona on the Thursday before the race. I traveled with a friend from my old NAC swim class, Paul, and his wife, Jacqueline. I got extra leg room on the plane, which at 5’7” I don’t need, but I like to be close to the emergency exits in case of the obvious. I don’t particularly like flying so it comforts me to be near the exits. However, at the exit, I also spend the entire flight mildly anxious with having to override the compulsion to pull the emergency door release at 38,000 feet, killing everyone on board, so it sort of balances out. I mostly just enjoy the bit where we get off the plane safely. We’d organised a mini-bus company to pick up and drop club mates, so it was nice to have transport waiting for us. We got to the hotel in good time and I checked in and headed to my room. The room was a shoe box with very little legroom. Seriously, it was the smallest hotel room I’ve ever seen. Richard Hart had disassembled my bike, which I’d brought with me, but I’d forgotten a particular Allen key that I needed in order to put the derailleur back on, so I just chilled that evening and grabbed food with Paul and Jacqueline. I slept like a log.

I’ve been told by colleagues that I should write a book of short stories compiling some of the stranger things that have happened to me. They do tend to happen with alarming frequency. I once woke up in a field in my underwear 4 km from home having been sleep-walking. I’ve had 3- too many embarrassing incidences involving individuals with dwarfism. The same person twice. I haven’t been able to get on the 5.15 pm train from Heuston station to Hazelhatch and Celbridge for the past 12 years because of an incident involving a blind man and I was once mistaken for a homeless person outside the Centra on Thomas Street while waiting for a colleague who was in there buying a chicken fillet roll. Registration on Friday morning could end up in this book.

On the Friday morning, I had a solid breakfast at the hotel and then myself and Paul went down to register. Paul went to the right side of the tent to register for the 70.3 distance, I went left to

register for the full. It was straightforward, more or less. Actually, it was definitely less. A very pleasant young lady scanned my entry QR code, checked my triathlon license was valid and verified my identity. No problem. I was well prepared. She put on my Ironman wristband and handed me a really nice bag into which I put my race number, 1019, and swim hat. This is where it got really awkward really fast.

She said “you can get your special needs bags over there on that table”, pointing to a table over my shoulder at the back of the room. I stared at her for just a second before saying “What?” She repeated herself almost exactly. “Over there, you can get special needs bags”. She pointed again.

I stared at her in confusion. She started to look uncomfortable. I took a step backwards and looked over at the table. Then I looked back at her. She was staring at me, but also smiling awkwardly. My mind started racing. What’s happening? Why is she saying I can get special needs bags? Had I accidentally checked a box on my application? Wait, there was a section on disabilities. What had I done? Why are you still staring at her. Just walk away. Not backwards. Stop walking backwards.

No, I didn’t check any box like that. I was sure I hadn’t. Why is she saying it then? I briefly looked down at my legs for some reason. I feel they’ve always looked a bit too skinny. Did my legs make me look special needs? I was looking at her again. Stop staring at her. Relax your face she looks uncomfortable. Jesus, STOP WALKING BACKWARDS!

I turned around at a speed that felt far too fast to look casual and walked over to the table very quickly. I absolutely must have misheard her. There were bags on the table. “Special needs bag – bike; Special needs bag – run”. What the f*ck? I grabbed one of each and walked off quickly, without looking back. I may or may not have thought to myself “what a cow**. Special needs.

Whatever”. Do not judge me, it all happened really fast, but that particular 12-15 seconds also seemed to stretch on forever and ever.

**this statement has been moderated. It wasn’t a ‘cow’.

I said nothing to Paul. After a quick stop at the Ironman village, trying to walk off the developing sense of PTSD, I headed back to the hotel to reassemble my bike. It was a bit tricky considering how small the room was. I had to put the bedside locker on the balcony and turn the single bed on its side just to be able to open the bike box and do the bike assembly. Fortunately, it went together rather quickly. Although I couldn’t quite tighten the handlebars up as much as I would have liked – they’d eventually loosen a bit during the bike arm of the race, but didn’t cause any major upset. I took the bike tags out of the bag I’d gotten at registration to apply them to my helmet and the bike. At this point I read the instructions in the race brief comprehensively, realising that every full distance competitor got ‘special needs’ bags and that they were used for certain items, like nutrition, pain killers, etc, that wouldn’t be returned to you, but could be picked up at certain points during the race. That poor lady at registration. As it turns out I’m some sort of beautiful bald himbo that should have been supervised.

Paul and I then went out for a 30 km reccie cycle, which was windy and wet by the end, but the bike stayed together and the gears shifted smoothly, which was a relief. Later that evening Eoin and Richie arrived, so I headed out with them to get some food. And wine.

On the Saturday, the day before race day, I accompanied Eoin and Richie down to registration. I was mildly apprehensive. Fortunately, I didn’t see that lady again. She had probably quit or was at a sponsored counseling session. They both seemed to be fully versed on the special needs bags. Following their registration, we had a walk around the Ironman village and Eoin picked up his bike from the rental shop. I thought the shop looked quite run down and nothing like the pictures on the website. As it turns out it had been gutted by a fire 2 weeks previous. We then went out for a 20 km cycle, so Eoin could test the bike.

In the afternoon we dropped our bikes down to transition. So many of the bikes looked so much more impressive than mine. This made me nervous. I tried not to think about it. We met up with some of the others, Paul, Eimear, and Mark for some group photos on the beach near the finish line, and that evening we had a carb-heavy dinner. Afterwards I went back to the hotel, re-checked that I was well-prepped, and went to bed early. I slept surprisingly well.

Sunday morning was race day. We all headed to breakfast at 5.30am. Richie, Eoin and Paul had decent breakfasts. Richie had mixed scrambled eggs and beans on a plate. It look absolutely gross. Just looking at it made me nauseous. I could hardly eat I felt so sick with nerves. I hadn’t been nervous up to that point. I had 3 spoons of sugar puffs but wasn’t confident I could keep any more down. Breakfast of kings. I went back to the room and double-checked my bag, then we headed down to the start area. I got rid of the rest of the gear bags, checked on my bike, and then started to change into the wet suit. Eoin and Richie were in good spirits, which helped distract me from how nervous I was.

We finally got down to the beach. This was it. We met up with Mark and his wife, Jen. I felt like I was the only nervous person there. Everyone else looked so calm and ready. They looked like proper athletes. The 70.3 competitors went into the water first. It was immediately apparent that there was a cross-current. It was useful to see that before I got in the water. I made a plan to adjust my course to compensate. Eventually, it was our turn to start moving toward the start line. I kept thinking that I still had time to get out of it. I just kept trying to reassure myself. I repeated to myself “If someone asked me to swim 4 km I could do that. If they asked me to do 180 km on the bike I could do that. If they asked me to run 42 km I could do that, probably. I can do this. It’s all achievable.” Still, it didn’t really help. Historically, I knew the only thing that would help was to just start the race. Just get to work and there’d be no space for nerves.

Eventually, I was being funneled into the main competitor channel, making my way toward the start line under the arch. The flow of competitors over the start line is controlled by several channels, each ending in a line of marshals with outstretched arms. The nerves were insufferable at this point. Soon there were only 3 people ahead of me. Goggles on. Competitors enter 6 seconds apart. Two people ahead of me. Watch ready. One person ahead of me. This is it. The marshal didn’t make eye contact. Her arms dropped. It was with a tremendous sense of relief that I pressed start on my watch and began running towards the water. Smile for the camera. I actually settled into the swim very fast. I’ve done a lot of open water. The body remembers, training kicks in. Everyone else seemed to be taking the wrong line, they were all drifting left. I sighted early and often. I forgot about the other competitors and just headed for the first buoy, correcting for drift. There was nobody around me. I got to the first buoy fairly quickly and because I was coming in at a different angle to most other people there was little interaction and I didn’t get any kicks or anyone crawling over me. I took a right turn at the buoy and headed into the current. The swim up to the next major turn was a bit of a slog. I stayed on the outside in clean water. I prefer to just chug along on my own, like a swimmy-no-mates, rather than draft. I know it’s probably inefficient, but it works for me. I enjoyed the feeling of the nerves having dissipated. At one point I went over a pretty small lion’s mane jellyfish. It missed my face thankfully, and as I felt it roll down the wetsuit I stuck both my feet up out of the water and just used my arms to paddle. I can only imagine it looked sexy. Fortunately, I did manage to avoid a sting. I find it can be very useful to sight two sequential buoys. It helps maintain a good swim line, and it did. Eventually, I turned left at the next major buoy, back into the cross current. The current here was a little different, but I managed to get to the next buoy fairly quickly and turned left again. The longest section was with the current, about 1.8 km. This section was easy, although the swell made it a challenge to successfully sight on the majority of attempts. Soon I was at the next buoy, rounding back into the cross current, again, chugging along. The turn right at the final buoy on the return to the beach brought the most challenging part of the swim. Lots of swimmers condensing into a bottle-necked stream. There were a few kicks, elbows, and blows to the head involved, but that’s what people get for crossing me (consider that a joke and it’s fine). Before I knew it, I was back up on the beach. For a moment I thought I’d exited at the wrong point, as there were so many people on the beach crowding the arch it was hard to see it. I finished the swim in 1:25:09. I’d hoped for 1.15, but reckoned that it would be closer to 1:25 with conditions as they were, so I was happy with it.

I trotted up the steep beach like a pony, but once off the sand, I walked into transition. My goal was to finish this Ironman and while everyone agrees that quick transitions can make a big difference to your time, I wasn’t going to rush. Not for my first full distance. In transition, I sat beside a guy who had had his front tooth knocked out in the race back up onto the beach. Don’t look at me. It was an implant, and he didn’t seem too upset about it. Although he mentioned that it had cost him three grand. Yikes. In for a penny in for a three-grand.

I made sure I packed my back pockets on the trisuit with extra nutrition. I was ready to get on the bike. The trek out of transition to the mount line was longer than expected, but before long, I was up on the bike, having spent 9 minutes in transition. Over the entire bike course, I kept an eye on my heart rate. I didn’t let it go over 140 bpm. I knew that was an effort I could sustain almost indefinitely with proper fuelling. The first few kilometres out of the town was no problem, but as I exited into the more open coastal roads the wind picked up significantly. It was tough going. At the 20 km mark, I had my first in-race confidence wobble. I was struggling into the wind, averaging only 24-25 kph. I kept thinking, “how am I meant to do this for another 160 km and then run a marathon?” I considered giving up, but I just couldn’t bring myself to do it. I wasn’t sore. I wasn’t sick. I wasn’t injured. I hadn’t had a mechanical. I had enough fuel and training. I was just finding it hard. “Idiot. It’s Ironman, it’s meant to be hard. Stop complaining and just turn the pedals.” Finally, I settled into it. I made peace with the fact that it was windy. Besides, it’d be nice on my back on the return. There were quite a few groups drafting. It was tempting, I won’t lie. But I ndidn’t want to get a penalty on my first full Ironman, and if I was doing this I didn’t want the effort tarnished by knowing I’d cheated. I wanted to do it exclusively under my own steam. Parts of the course wound back and forth and at the 54 km mark was a 1 km climb. It wasn’t too bad, I passed lots of people, but you did feel the heat. The next 36 km back to the start of the loop I just cruised along, allowing myself to enjoy the lack of headwind. My fuelling was good, but I picked up two bananas and extra electrolytes, as I knew with the headwind that I was going to spend longer on the bike than I expected, and I needed to conserve gels. God, I hate bananas so much. I mean, I know they’re good for you, but it just seems too much when you’re already committed to destroying your body on the day.

Eventually, I got to the half-point turn, 90 km down, 90 km to go. I didn’t feel so apprehensive about the headwind, knowing I’d only have to suffer it for 54 km. While the wind had actually picked up for the second loop I felt stronger on the first 20 km of that second loop. Not surprising considering that the legs had just spent 36 km cruising back at the end of the first loop. They were primed, ready to go. The second loop was fine if you ignore the mentally ill bits…

On the second loop, I developed a bit of a peculiarity. Generally, when people would pass you on the bike they’d say “hi!” or offer words of encouragement and camaraderie. I liked this. However, sometimes people would go by you, slow enough for you to say “hi” or “how’s it going?”, and they’d ignore you. They’d just look at you trundling along on your road bike, turn their heads away, and continue. They’d usually have very nice TT bikes. I did not like this. When this would happen

I’d look at their names, fluttering about on their backsides, and say them out loud like a proper psycho. Gus. Orlando. Ruiz. Peter. Iron Joe. Colin. I’d remember what kind of gear they were wearing. I’d make a mental note to say “keep going, you can do it”, very derisively, when I’d ultimately claim them one by one on the run. And I did catch them, every single one except Ruiz. Completely normal, rational behaviour. Perhaps I really do have special needs. Or an electrolyte imbalance.

On the second loop I also spotted Richie once, but nobody else. I shouted “Richie!” and he hollered back in his usual playful style, so young at heart, like Benjamin Button, but from Dublin 9. In the last 25 km of the cycle I noticed the other side of the road was now clear. There were no more competitors. It made sense, but at the time I remember being worried about whether I’d make the cut off and why I let so many people pass me. Yes, it was probably an electrolyte thing.

I got back into transitionand I was relieved the bike was over. I’d finished it in 6:35:13. Now I just had to run a marathon. Except it wasn’t a marathon, not in my head. It was 8-and-a-bit parkruns. After 8 minutes in transition, I was ready to run. I took two painkillers, as my right leg had been aching and acting up for a week before the race. I took a right out of the transition area and started to run.

The plan was simple. Run at 5.30 per km, trot through all 21 aid stations, alternate electrolyte and water, douse myself with water to keep cool while the sun was still hot, and keep the heart rate under 140. No stops. Smoke Gus, Orlando, Ruiz, Peter, Iron Joe and Colin. They were compensating with those fancy bikes. Yes, dear reader, I am a slightly vengeful person. I also collect stamps.

As it turned out the run was the easiest bit. I chugged along, everything went to plan pretty much. Two kilometres in and I was aware the leg was aching. This was worrying, as I wasn’t sure how it would fair over another 40 km, but fortunately, it didn’t get any worse. I started the run at around 5pm, so the heat wasn’t too bad at all, and it only got better. On the first 10 km loop I saw Eimear, who had signed up for the 70.3, but unfortunately didn’t complete it, and Mark O’Brien gave me a cheer. Mark hadn’t felt well on the bike and had thus retired. Some people make good, sensible decisions. Others memorise the names of innocent, unsuspecting competitors and try to outrun them, like a bona fide lunatic.

At 10 km I started to feel more confident about my ability to finish. I reckoned if I could definitely run half the distance I could walk the rest if absolutely necessary. The level of support from the crowd during the run was fantastic. There were lots of Irish there to cheer you on and make a fuss. At the 25 km mark, the battery in my watch finally gave up and went dead, so I had to rely on perceived effort to stay on pace. It was fine. By that stage, I was in a rhythm. It was in the latter half of the run that I start to pass competitors with recognised names and trisuits from the bike section. Some were still trotting along, some were walking. Part of me took pleasure in passing them. But it was only the small, petty part of my personality that enjoyed it. Gladly, and with no small amount of relief, I found myself calling their names as I went by them, genuinely encouraging them to keep going, reminding them we were nearly there. Everybody has their reasons for being there, for traveling from all over the planet to undertake a massive race. More than once over the day I thought about what that means. An invisible thread of competitive spirit, collegiality, and mental cooperation that winds its way through us all, connecting us, and driving us forward. It felt right to want everyone to do their best and to help them cross the finish line, even if it was by offering only a few thoughtful words.

Once or twice, I encountered Eoin and Richie, coming the opposite way, getting and giving encouragement. At one point I caught Richie and enjoyed wiggling my thumbs at him. In the days leading up to the race, I had been worried my leg wouldn’t hold out for the run and that I’d have to retire. So much like a poet, Richie had said that he’d insert his thumb up my backside to drag me over the line if he caught up with me. An inspiring incentive to keep going. We ran side-by-side for a little bit and when he was sure I was going to be ok, he dropped back for a loo break. Later on it started to get dark, and on certain sections of the run, you had to watch your footing. I was running well but by about 35 km the legs were definitely starting to tire, and the seam on my new tri suit had chaffed into the backs of my knees quite badly. They’d take weeks to heal. But I still felt good so I made a deal with myself. At the 37 km mark, I’d take a 90-second walking break, leaving myself just one parkrun distance to go. It was a great 90-second break, although the legs protested a little at having to restart and I found myself audibly speaking to them, telling them we were going to make it, we were almost there. Perfectly normal behavior. With 2 km to go, I could see the lights of the finish line and decided to put the foot down and empty the reserves tank. I picked up the pace and was running at maybe 4/4.15 per km. The adrenaline kicked in. I flew by the last aid station, not bothered with it. In the last 150 metres I readjusted my pace so that I wouldn’t be on top of anyone coming down the red carpet. I merged in behind a runner about 25 m ahead of me and was soon running down to the finish line.

The lights were dazzling, the music loud and a voice said “Steve, you are an Ironman”. I remember excitedly saying “yeah I am!” as I went by, high-fiving a guy with a microphone. I remembered to get a good pose coming across the line. That’d be for Strava. It was done. It was over. I was finished. 12:27:06. I got the medal, picked up my t-shirt, and went into the finishers’ tent for some food.

They had plenty of food and beer on a self-service tap. It was Heineken. I wasn’t that desperate, so I had a non-alcoholic. I sat with a few lads from another club, as Richie and Eoin were still out there, and thought about my life choices. Eventually, I started the walk down to transition to pick up my bike and bags. I kept an eye out for the lads but didn’t see anyone on the way down. On my way out of transition, I saw Richie go by alongside another competitor, encouraging him to

keep going and chatting away. The man didn’t look like Richie had violated him with his thumb. I shouted “well done!” and he waved. He only had 2 km to go. He was always going to make it. I thought about sticking around waiting for him and Eoin, but I had the bike and all the gear, so I walked back to the hotel. It took me an hour and a half less to find the hotel this year compared to last when I did the 70.3. I had texted people to let them know I was alive, was showered, and passed out on the bed within 30 minutes. It was surprising the places that did and didn’t get chaffed.

The following day would be spent in merriment, having food and beer and talking a lot about our individual experiences. Any time Richie has drinks he gets a bit hyper, moreso than usual, and he reminds me of Fr Purcell, one of the characters in Father Ted. Have a look and judge for yourself… https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z88AiJtZpZI. I do a fairly good impression, which kept Eoin well entertained.

Ironman Barcelona was my first Ironman, but hopefully not the last. I learned a lot about mental and physical endurance, about teamwork even when you’re on your own, and about myself, not all of it pretty. It was very challenging, entirely achievable, and very rewarding. As the Roman philosopher, Seneca said “Luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity”. Doing an Ironman requires a little bit of luck, but Seneca’s wise words remind us that you make your own luck. Mostly you just have to do the work, trust the plan, and have a bit of faith in yourself.

Wow, just read your incredible column out loud in the car while driving back home from two holiday/training weeks in Spain in preparation of the Ironman Barcelona 2023. We laughed and we cried. Thank you so much for writing this. Regards John and Linsy

Great read Steve

Well done on completing your first Ironman

Looking forward to sharing the Barcelona experience with you and the the Tritanium Team this October